Happiness, or subjective well-being as some refer to it, has long been associated, on some level, with beneficial health outcomes at the individual level.

There are a multitude of studies that have shown a relationship between an individual’s subjective well-being and some measure of improvement in overall morbidity or mortality. Simply put, we know that happier people have been reported to be healthier people.

But, then, why is everyone in healthcare so miserable?

I mean, patients are unhappy with the whole thing – prices, access, quality of care. I cannot recall a single chronic patient that I have ever met who has raved about the health system and how efficiently it operates. Occasionally, one will meet a patient who went through an acute scenario and was pleasantly surprised at how it turned out.

Caregivers are exhausted and equally disconsolate with the never-ending red tape of insurance paperwork and lengthy wait times as they shuttle their loved ones to and from appointments. Doctors are burnt out and despondent with a system that is nothing like they imagined. Ditto for nurses and pharmacists. Politicians are exasperated with spiralling costs and voter backlash at every turn.

Insurance companies and pharmacy benefits managers are crestfallen at the venom directed their way as they are blamed for the egregious costs being imposed on the system. Patient advocacy groups, while doing incredibly important work, often struggle for funding and to find a clear voice that resonates and can move the needle on meaningful policy change on behalf of their membership.

And manufacturers – both medical device and pharmaceutical – are no less miserable as they face a barrage of questions from lawmakers about their costs and pricing practices, and a slew of disapproving looks from the general public about their perceived greed and callous approach to patients’ lives.

In 2018, See and Yen published a paper showing that happier nations have better health system performance as measured by efficiency. They used the ‘happiness index’, which is a comprehensive indicator that includes

several important components, such as caring, freedom, generosity, honesty, health, income and good governance. And they measured efficiency as a function of life expectancy and inverse mortality rates.

The findings show that happiness is one of the factors that contributes to the efficiency of a country’s health system. Others have also published similar results on the topic of happiness and health.

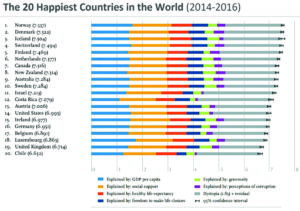

And then there’s the United Nations 2017 World Happiness Report (see chart), which shows that among the top 20 happiest nations on the planet, a healthy life expectancy matters in the overall ‘happiness equation’ but accounts for less of a nation’s overall happiness than, perhaps, we think.

This doesn’t necessarily contradict any of the peer-reviewed work out there, as the empirical data is very clear that happiness is only one of the factors associated with health and health system efficiency. What the UN World Happiness Report reinforces is that the impact of happiness might be even less than we think.

Of course, there are methodological issues with all these papers and reports. How do we measure happiness? And how do we measure both health and health system efficiency? Is there an inherent selection bias in our data? Or other biases that we are not aware of?

But it is all confusing, isn’t it? If happiness is important at an individual level and a societal

level in contributing to population-level health as well as overall health system efficiency, why are so many people so unhappy with the state of healthcare. And if so many people are unhappy with the state of healthcare, how is it that we are producing this efficiency in certain countries?

Maybe, the answer is that other variables related to happiness (like income, education, housing, good government, security, religious freedom, etc) mask or overwhelm the low numbers associated with happiness from healthcare.

Or maybe there is some reverse causality happening – it’s not entirely that happiness leads to a healthier life and a more efficient health system but that a healthier life and a more efficient health system lead to happiness.

Regardless of these important nuances, I have not been able to find any stakeholder group that is truly ‘happy’ with the state of healthcare today. I’m betting you haven’t either.

How come I can’t find anyone who is ‘happy’ with healthcare?

This article was originally published here.