It’s hard to take something away once you’ve given it to society. It’s even harder when you have no back-up plan. This is the undeniable lesson from the Obamacare debate that we’re witnessing.

It’s hard to take something away once you’ve given it to society. It’s even harder when you have no back-up plan. This is the undeniable lesson from the Obamacare debate that we’re witnessing.

At a macro level this is true of the entire Affordable Care Act unto itself as Republicans are finding out. It’s not easy to just make an entire piece of legislation that accounts for 20% of total gross domestic product (GDP) go away. But it’s also true of the individual elements and clauses within the act itself. Pre-existing conditions: don’t touch that! Children covered on their parents’ plan until the age of twenty-six: need it. Federally established essential health benefits and services: an absolute must. If Republicans are to succeed (or, for that matter, if any political party in any jurisdiction is to succeed in this type of bold attempt to overturn a previous administration’s legislation), the focus needs to be on ‘building upon and improving’ instead of ‘repealing and replacing’.

This is as much a lesson in communication and the subtlety of language and word choice as it is about astute health policy, navigating the corridors of power and working in a bipartisan manner. By articulating words like ‘repeal’ and ‘replace’, there is a palpable sense of a void and a hole. And with it a connotation that is inescapable: that repealing and replacing implies I must give something up. To be clear, the use of different words probably would have made a very minor impact in the whole debacle that was the Republican strategy. There still needed to be an actual ‘plan’ that made sense. And there wasn’t.

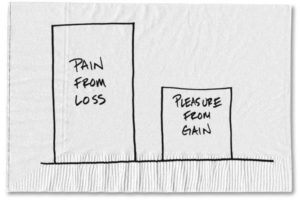

The behavioural sciences have taught us for decades that ‘taking things away’ elicits a very strong reaction in people. Loss aversion is what we call it. And empirical studies have shown that it’s about twice as powerful psychologically as the prospect of gaining something. And those same behavioural sciences have also taught us that language and words can be critically important drivers of behaviour. It’s bizarre that a president who has used psychology and communication as effectively, if not better, than anyone else who has occupied his seat missed this one.

Before Obamacare became the law of the land, we knew that loss aversion in healthcare was a political hot potato. A survey experiment in 2009, in the midst of the debate over healthcare reform, provides an illustration of loss aversion within the context of health insurance. Respondents to this survey were randomly assigned to one of two different scenarios and then asked to make a hypothetical choice between two healthcare plans (see above).

In both cases, the absence of a lifetime limit on health insurance benefits will cost the respondent $1,000 per year. In the first scenario, the cost will come by foregoing the savings of a plan with a lifetime limit. In the second scenario, the cost is directly tied to the lifetime limit. However, despite the equivalence, the different framing of the options (one emphasising ‘savings’ with the other focusing on ‘cost’) is critical. This example is illustrative of what we have always known (except for a few Republicans in the US apparently) which is that the framing of choices and the presentation of such choices as ‘costs’ vs ‘savings’ can greatly impact perceptions and behaviour in healthcare.

And so, in the end, we continue to regard our neighbours to the south as being caught in an echo chamber of sound bites emanating from two political parties whose views on healthcare are so fundamentally different. The lessons we learn do not stop with loss aversion. Social and public health policy does not afford us the luxury of thinking about the heterogeneity of healthcare. We cannot think of the ‘ones and twos’ in society. We need to take something heterogeneous and treat it as though it were homogeneous. This is hard. Every nation struggles with this harsh reality. And, to be fair, no single nation has managed to get it right. The outside view, however, is that our American neighbours struggle more deeply than others. Perhaps it is due to partisan politics and political myopia.

Or perhaps it is due to ignoring the most basic lesson of them all: if you have your health, nothing else matters. If you don’t have your health, nothing else matters.