This is not what Richard Thaler had in mind. Nor Daniel Kahneman. And certainly not Steven Levitt. The behavioural revolution was supposed to be impactful. It was definitely going to weave its way into our everyday lives. It would change the way we looked at and consumed food and how often we exercised and how we saved money. But it was not meant to save the world.

With the arrival of COVID-19, we have seen a slew of behavioural health ‘nudges’ emanating from hundreds of countries around the world that are, literally, a matter of life and death.

Stay at home. Wash your hands. Sneeze into your elbow. Practice social distancing. Shelter in place. Don’t shake hands. Don’t hoard food or medicine.

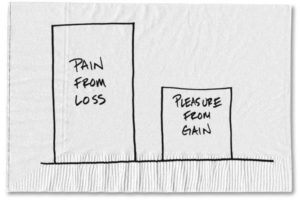

There is no question that these are the right principles for all countries to be adopting. The important question is how we make them ‘sticky’ without mandating citizens to do them. Without rolling tanks into the streets and imposing curfews and martial law. After all, when the government forces you to do something, this is no longer a behavioural nudge. And underpinning this large question around ‘stickiness’ are some of the smaller more nuanced questions that we need to consider: does expected utility theory still hold true in the case of a global pandemic? In other words, do decisions made under conditions of uncertainty about expected outcomes (becoming infected) and the hope that people behave rationally still apply when everyone has the same uncertainty? Or maybe everyone doesn’t have the same uncertainty about expected outcomes. Maybe some people know more than others. In which case, how does information asymmetry affect this pandemic and people’s behaviour?

You may recall that a few months ago (in PME, October 2019) I wrote a column about externalities and their importance in the context of public health. The notion that your behaviour has an impact on my health. In that column we talked about negative externalities (second-hand smoke) and positive externalities (vaccination or immunisation providing herd immunity). Today this concept, intertwined with the larger idea of ‘nudges’, is truer than it has ever been in modern times. Everything that everyone does has an impact on everyone’s health. Externalities are the new normal.

And what of another favourite topic of mine, health literacy? Telling people to ‘shelter in place’ is all fine and well. But do people know what this means? Does everyone have the same understanding of this concept? And, as a ‘nudge’, how do we actually accomplish this? Why is this important? Because research shows that people who are better informed about their health status are more likely to have better outcomes. In fact, let me be far more precise: differences in health literacy levels have been consistently associated with increased hospitalisations, greater emergency care use, lower use of mammography, lower receipt of influenza vaccine, poorer ability to demonstrate taking medications appropriately, poorer ability to interpret labels and health messages and, among seniors, poorer overall health status and higher mortality¹. In this current COVID-19 environment, with the exception of mammography use, all of these associations between health literacy and outcomes are strikingly important.

Another long-standing issue that I have championed for years is also critical at this time – the use of Dr Google to search for online health information. Many readers may be familiar with my views on the subject and, specifically, how the practice of seeking health information online can adversely affect access to care, treatment decisions and allocation of scarce resources. The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened my concerns in this regard with a veritable deluge of misinformation being spewed forth on a daily basis (particularly as it relates to treatment options for combatting this virus). How do we counter some of the dangerous and non-scientific data that is being disseminated? And, more importantly, how can we nudge tech companies to limit misinformation which is proving to have found an incredibly fertile host on the internet?

With millions expected to be infected and, unfortunately, tens of thousands expected to succumb to this terrible virus, the COVID-19 pandemic will change the way we conduct our lives forever. There is no doubt about this. The use of behavioural nudging and its incorporation into public policy is here. But, in its current format as a blunt instrument of direction to millions of people, are we using it the right way?

¹ Berkman ND, et al. Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 199. AHRQ Publication Number 11-E006. Rockville, MD. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2011.

With COVID-19, society’s ability to adapt to behavioural measures is a matter of life and deaths

This article was originally published here.

It’s hard to take something away once you’ve given it to society. It’s even harder when you have no back-up plan. This is the undeniable lesson from the Obamacare debate that we’re witnessing.

It’s hard to take something away once you’ve given it to society. It’s even harder when you have no back-up plan. This is the undeniable lesson from the Obamacare debate that we’re witnessing.